Welcome to the Realities of Viet Nam

or

What They Didn’t Tell You Back in the World.

We all have a lot of fond and not so fond memories of Nam and among them was the equipment that we carried to assure our comfort and survival. Here is a review of some of them you may remember carrying around on your back.

Ruck Sack:

The supply Sgt. told me that I would probably want to buy this piece after my

tour so I could have the pleasure of cutting it up into small pieces because it

would be kicking my ass for the next year as we humped throughout the AO. Boy,

was he right! It was hard to imagine that we would pack 50-60 lbs. of crap on

that thing and tote it around with us everywhere.

This is the first rucksack I carried in late 1968. The only problems were that rivet on the cross member that dug into your back, and the lack of a frame, which made carrying the additional stuff, like radio batteries, ammo cans, flares, mines, etc. very difficult.

I finally got this external frame rucksack in early 1969. It was much better than my old internal frame pack. For one thing, it had a quick release on one strap, which could be a life saver in a sudden firefight. I usually attached my sack to the top of the frame, so that I could tie on the radio batteries, flares, etc. to the bottom of the pack. It also helped keep the main gear sack out of the mud. This pack weighed anywhere from 55 - 90lbs. on a normal three day march. I remember being unable to get to my feet with the rucksack on, without someone else giving me a hand. Some people like my Medic Doc Miller, carried even heavier packs. This is the medical bag he humped in addition to his normal rucksack.

I constantly asked him to lighten his load, but he said that he needed

everything to keep my people healthy. I can't believe he could carry such

a load. On tough marches, I used Doc as a guide to let me know how fast a pace

to set.

Steel Pot:

No one wanted to wear this damned thing, it was hot and heavy, nearly

3 pounds. Beyond the obvious safety feature, our “steel pots” could be used

to quickly dig a slit trench if lead started flying or most often used as a wash

basin. I believe the order of events were wash face and hands, then shave and

finally wash out socks all with the same water. I also used my outer shell, the

"steel pot" to cook stews out of the left over, undesirable C-rations. We

understood the reason for them but left to our own probably would have chucked

them and taken our chances. In fact most soldiers carried a "Boonie Hat" stuffed

in their rucks, which they put on as soon as they got out of sight on a patrol.

The Boonie hat was comfortable, quiet, light weight, and permitted better

hearing than the regulation helmet.

P-38:

Probably the most important survival tool we had was the remarkable P-38 can

opener, without which we would have starved. I kept one on my dog tag chain

because trying to locate an opener in the dark could be challenging.

Remember the delights of C-rations???

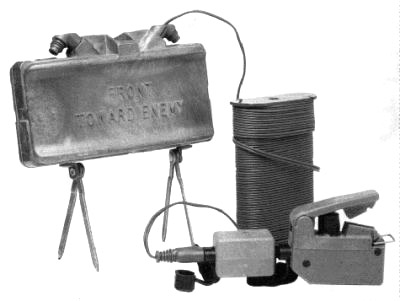

The heat tabs were OK, but made an acrid smoke that was worse than tear gas. Most guys cannibalized a claymore mine for the C-4 explosive and burned it. I personally preferred to use a small piece of Flex X, a sheet explosive used for cutting steel.

Below is the standard issue blue trioxane heat tab...

Entrenching Tool:

This little shovel/pick/hoe was an amazing tool. I believe that we must have excavated

enough dirt and filled enough sand bags to dig another Panama Canal. It also was

used to create a convenient toilet regardless of your location. In 1968 almost

everyone carried the wooden handle, folding blade entrenching tool shown below.

By 1969 many carried the newer all metal folding model.

This folded down to the size of the blade, but was not as sturdy as the wooden handle model, so many opted to keep the old rigid wooden handle tool.

Machete:

Like the trenching tool what we accomplished with these things still amazes me.

I can remember landing on a bombed out hill top with trees and stumps lying

every where and we would build a firebase with basically our entrenching tools

and machete's. We

hacked trails, cleared firing lanes and if really unlucky used them as weapons.

Some of the hardwoods were so tough, that they would break out a half moon chunk

of the blade if you struck them wrong. Blisters were a normal condition

for those who used the machete.

Mosquito Net, Air Mattress, Poncho, Poncho Liner:

Once the mosquito net got wet and you had to carry it, it was gone. It was undoubtedly the most useless item that we were issued. The only time we saw then was on the folding cots and bunks in base camp.

The air mattress was a great idea but the thought of carrying it and then having to blow it up each night made this item disposable too. During the monsoons, if sleeping on an air mattress you had to tether yourself or windup floating out of the tent into the rain and maybe out of the perimeter.

The poncho was definitely a great piece of equipment. However, like many things designed to do multiple functions they wind up not doing anything very well. Wearing one during the monsoons only served to keep the rain off your shoulders but because it was so hot you sweated so much that everything was soaked anyway. As a shelter half it was too short to be able to get both your head and feet inside of it. If needed it could be made into a stretcher or a makeshift body bag.

While some of us actually humped wool blankets for those wet cool mountain nights during the winter monsoon, it got really heavy when wet, which it was all the time in the field. It did keep you warm though, even when wet. Later we discovered that everyone in base camp had the new nylon, fiberfill poncho liners that weighed practically nothing when wet and were just as effective as the heavy wool blankets. A few threats to send everyone to the field got them issued to all troops bound for the bush from then on.

Uniforms:

When I arrived in the field I was told to get rid of my underwear and go

commando. I thought that this was pretty uncivilized until after a couple of

days of constant wear it just sort of disintegrated. I’m not sure what was the

longest stretch we went without getting clean uniforms but I believe that it had

to be weeks. Most times our fatigues were not even close to olive drab in color,

more sort of a faded reddish brown. I would challenge anyone to pick out

someone’s rank based on their uniform. It was not advisable to advertise your

status to the bad guys. Not only did we not wear any insignias of rank, saluting

was out of the question. The RTO’s hid the radios in their backpacks so not even

the antennas were visible. The medic’s kits were pretty hard to disguise so they

unfortunately were targets of opportunity.

The shirts and fatigues during the 1968 time frame often came with buttons. Buttons that seemed to catch on everything in the bush. Buttons and that came off far to frequently.

Later issues had replaced the buttons with Velcro.

Boots:

The Army issued jungle boots were a dramatic improvement over what we wore

stateside. Unfortunately because our feet were wet a lot of the time and we

almost never got to take them off strange things happened to our feet. I

remember seeing guys with green toes, ugly blisters and assorted maladies that

got them removed from the field, which created an incentive for not taking care

of ones feet. You could tell an infantry field soldier from all of the other

base camp weenies by the condition of their boots. The guys in the field had

boots that were completely void of any remnants of black while the guys in base

camps had their boots polished every day. I returned to Pleiku on my way to R&R

and stayed in the BOQ. When I woke up I found that the “mama san” had polished

my boots like she did for all of the base campers. I believe that I took a steel

brush to them to get them back in shape.

It could have been worse, we could have been issued Ho Chi Minh “ridge runners” made from old Goodyear or maybe Michelin tires. I must admit, I do own a pair of Keen sandals that could easily pass for Uncle Ho's originals.

Compass:

You had to remember that a compass never lies! The problem was the maps we used

to guide ourselves were so inaccurate that it made the compass irrelevant most

times. We relied on the “Arty” guys to tell us where we were most of the time

and hoped to hell they knew where we were because you didn’t want to wind up on

the Gun-target-line, those short rounds could ruin your entire day.

Canteen:

When I got there in 1968, all I was issued was the standard 1 Qt. Army Canteen shown below.

In the heat of the dry season from November through May, the temperatures were often hovering around 100 degrees Fahrenheit, with average temperature for April at 87 degrees. On occasion I have seen temperatures exceed 110 degrees. So hot that a weapon left in the sun for only ten minutes became so hot that it would raise blisters if you touched the metal parts to your bare skin. Climbing thousands of feet up mountains, through thick jungle and often slippery clay soil, with your 60 - 90 lbs. rucksack on your back, you had difficulty carrying enough water in the 1 Qt. canteens. Fortunately, by 1969 most of us had one or often two of the collapsible bladder 2 Qt. canteens, in addition to our regular 1 Qt. model.

Most of us still kept the 1 Qt. canteen, because the steel cup, which lined the canvas cover and was valuable as a cooking pot.

Gas Mask:

The M17A1 protective mask was carried because we often had to go into areas where riot or tear gas had been used. I believe this mask weighs just under 3 pounds and it used two replaceable filters, one in each cheek pouch..

On at least one occasion I remember having to use them to be able to breath, when a Chinook double rotor helicopter was spraying herbicide along the highway, and the wind shifted blowing it all over my unit. It was so heavy, that the filters in the masks got clogged and we wound up breathing through spare socks or t-shirts. Afterwards several of my men became nauseous. We were moving away from the highway into the bush, and had to wear those herbicide soaked clothes for nearly two weeks, before we reached a landing zone, where we could get clean clothes flown in to us. Any one who remembers that incident please contact me.

Insect Repellent: N,N-Diethyl-m-toluamide 70%

In the jungle, this was an essential supply. Even with it, the mosquitoes ate you up. Malaria was a constant threat and mosquito bite fevers were routine among the troops in the jungle. In a pinch, you could also mix it with peanut butter for a fuel tablet substitute to heat your C-rations.

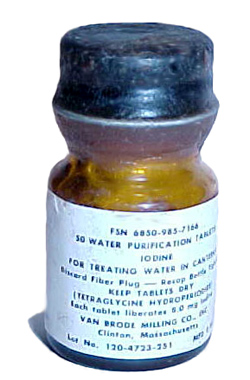

Water Tablets: Iodine

Since all water, even that in villages and towns must be considered suspect, we all carried bitter tasting Iodine water purification tablets. It tasted nasty, but dangerous to drink water not treated with them, even if the streams in the mountains looked crystal clear. The NVA would often throw the carcasses of dead animals in the water upstream of a firebase in an attempt to create casualties.

Sand Bags:

When I got in country in 1968 we were issued cloth sandbags like the one shown below.

They were perfect, but would eventually rot, if left in place such as in a command bunker in base camp. Later we were given the "new and improved" nylon sandbags like those shown below.

These did not have the rotting problem, but during the monsoon, they could slip as the clay they were filled with got saturated, and you would wake up buried under the collapsed wall of your bunker. I personally preferred the cloth bags.

Flashlight, Right Angle:

In order to read a map in a bunker, under a poncho on the trail at night, or even sometimes in daylight under the triple canopy jungle, the military flashlight was required.

This model had several plastic lens covers that could be inserted between the bulb and the front of the lens cover. The red filter allowed you to use it without losing all your night vision. There were several other filters, but the only additional one I remember was a white filter that cut down the brightness of the bulb.

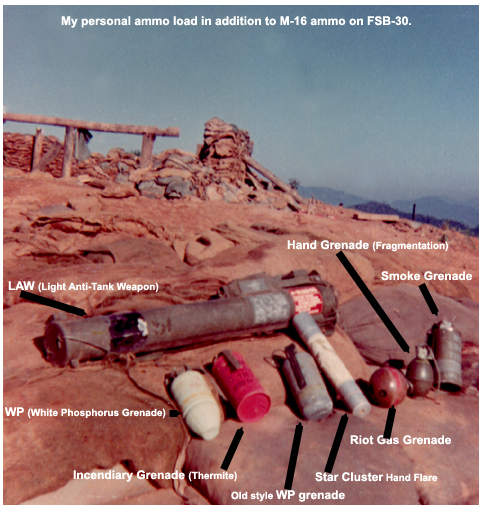

Ammunition:

We also were often issued the old style fragmentation grenade know as pineapple grenades as shown below.

Someone in each fire team also carried the Claymore Mine shown below.

You may remember using strobe lights to mark the perimeter when you called in the gun ships at night. The unit shown below is what we used, but the problem was getting the special mercury batteries for them. Most of the time we had to resort to building fires in the bottom of our fox holes.

Footnote:

I collected most of these images over the last couple of decades, and do not

remember where most of them came from. If I stole it from you, let me

know. I will remove it, or give you credit and put in a hot link to your

pages. Sorry, I never expected to be publishing a website.

Ken Groff is the main driving force behind this page. His narrative and memory, plus some of my own combined to produce this section. Hope you like it. If you have any more ideas, memories, images....

All Email addresses are in picture format only to discourage web bots from harvesting for junk mail lists. Type them into your mail manually. Site designed for Internet Explorer Version 6.0 or higher, viewed with text size medium and desktop resolution of 1024 x 768 pixels.

Webmaster:Homer R. Steedly Jr. (Email: Swamp_fox at earthlink.net) Copyright 08/12/1995 - 10/19/25. Commercial Use of material on this site is prohibited.